Rome to Fayetteville: Reflections on the Theme of the Nude in Art

On May 17, 1999, my wife and I were invited to attend a private tour of the newly renovated Archaic and Classical Greek galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This occasion was sponsored by the Society of Fellows of the American Academy in Rome, an institution were I had spent two and a half years, from 1976-79, The museum setting was majestically austere and was lit with a beautiful natural light which shone through the museum’s recently restored skylights.

I found myself face to face with a male standing nude – a Kouros figure. This example of 6th century Greek sculpture, created approximately 2500 years ago, can trace its roots back to the beginning of Western figurative art. It was influenced somewhat by Egyptian art, but the back pillar was eliminated and we have here man’s early attempt to create a full scale independent standing figure.

In the Met’s spacious galleries, I was mesmerized by this ancient Greek sculpture and, in turn, found myself thinking of Fayetteville, Arkansas and of the curator, Rebecca Johnson’s, request that I comment on the importance of the nude in both Western art and in my own work. She wished to have my thoughts on this subject available for visitors to my upcoming retrospective exhibit. I looked back at the Kouros and was struck by this early attempt to reach for the essence of a vital and free-standing human being.

My mind wandered to later Greek and Roman sculpture, bringing to mind the Dying Niobid, the Discus Thrower, The Boxer, and the Ludovisi Throne in Rome and the Aphrodite of Melos in Paris. These are fantastic, glorious attempts to see and depict the nude, both in male and female form. In these examples, the nude is seen as our prototype, the measure of the human being in Western art.

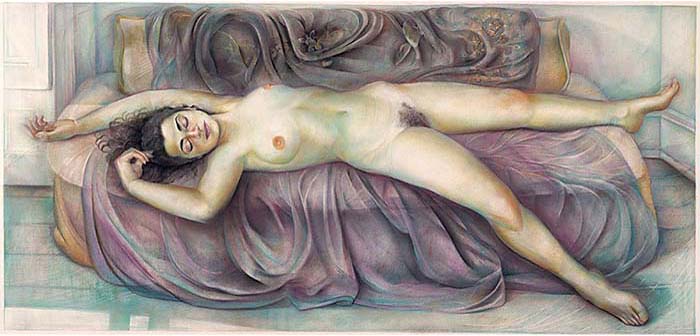

Later, in the 19th century, wonderful paintings of the nude by artists such as Manet, Goya, Corbet, Gauguin and Ingres provided another, more sensual, variation of this theme.

For myself, a crucial turning point in terms of addressing the genre came in 1988 when I visited a wonderful large-scale Degas exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum. This magnificent show, full of spirit and verve, emanated a tremendous life force. Room after room were filled with exciting and sparkling work which pulsed with great humanity. Then one came upon a large room filled with images of the female nude, each one bursting with drama, sensuality and mystery. It was almost as if Degas had set himself the goal of taking the great and classic concept in Western art of the nude and seeing where he stood in terms of this theme. It was a room full of powerful and expressive pastels, drawings and paintings and it was a strong tribute to both the subject matter (the nude) and to an artistic attempt to bring to this theme a fresh energy and life force.

In addition to the Degas show, a number of contemporary exhibitions have influenced my thinking on the subject of the nude. These include a retrospective of Balthus, as well as Lucian Freud’s major shows in Washington, D.C. and New York. Also, I would mention the very interesting discussions of the figure in art in Janet Hobhouse’s The Bride Stripped Bare and in Guy Davenport’s A Balthus Notebook. Hobhouse, in particular, describes and illuminates examples of this theme in the work of Modigliani, Spencer, Maillol, Schiele, Matisse and Picasso. She is very perceptive about the way our 20th century has intersected its character, urgency and sense of “modernism” into this theme.

So, as I looked at the Kouros, I saw a long tradition of artists dealing with the male and female form. I saw constant change and variation and each century’s ‘take’ on this ancient of forms. I saw, too, my own recent work and could not help wondering how my efforts will fit into this long, rich and romantic tradition.